Hello! This is The Accidental Birder, an illustrated memoir where travel, birds, and love converge into illustrated essays. If you missed previous chapters, you can start from the beginning here.

On an early autumn Saturday morning, we drove across the 7-mile causeway. Mountains reflected upside-down in the Great Salt Lake, and the brisk October air soothed my face.

“Slow down a little bit here,” Steve said, scanning the water with his binoculars, looking for birds.

This was our third date since we first met in Scotland. A couple months later, we spent a week in England’s Cotswolds—our second date. After he moved back to Toronto that fall, he wasted no time booking a flight to see me. I was excited to show him my hometown.

I picked Steve up at the airport and brought him home, where he sank into my couch and put his socked feet on the ottoman. I curled up under his arm like a cat.

“I have some ideas for this week,” I said. “But is there anything you want to do?”

“Let’s go to Antelope Island.”

“Really?” I’d lived in Utah for ten years and never once visited Antelope Island State Park. Why would you want to go there? I thought.

People typically want to visit Arches, Zion, or Bryce Canyon National Parks when they come to Utah—not a fifteen-mile-long island in the southern end of the Great Salt Lake. I’d flown over it countless times, but from my window seat, it always looked like a small, unremarkable hilly, brown mass in the lake.

The towering Wasatch and Oquirrh Mountains surrounding the valley dwarfed the island. Great Salt Lake wasn’t suited for boating, water skiing, or fishing. It was too shallow, and there weren’t any fish. Its rotten-egg stink sometimes hung in the air throughout the valley, making Steve’s interest in visiting even more surprising.

“There are great birds there,” he said. “Got a map?”

I found one and handed it to him.

“I love maps,” he said as he spread it on the floor and lay on his stomach studying it. I walked to the kitchen to make dinner, passing Steve’s suitcase. His tripod and spotting scope were propped up next to it, and I silenced the niggling question in my head that asked if he had come for the birds or for me.

At the northernmost end of the island, we stood on the side of the road next to my car as Steve pointed to some birds floating atop the water close to shore.

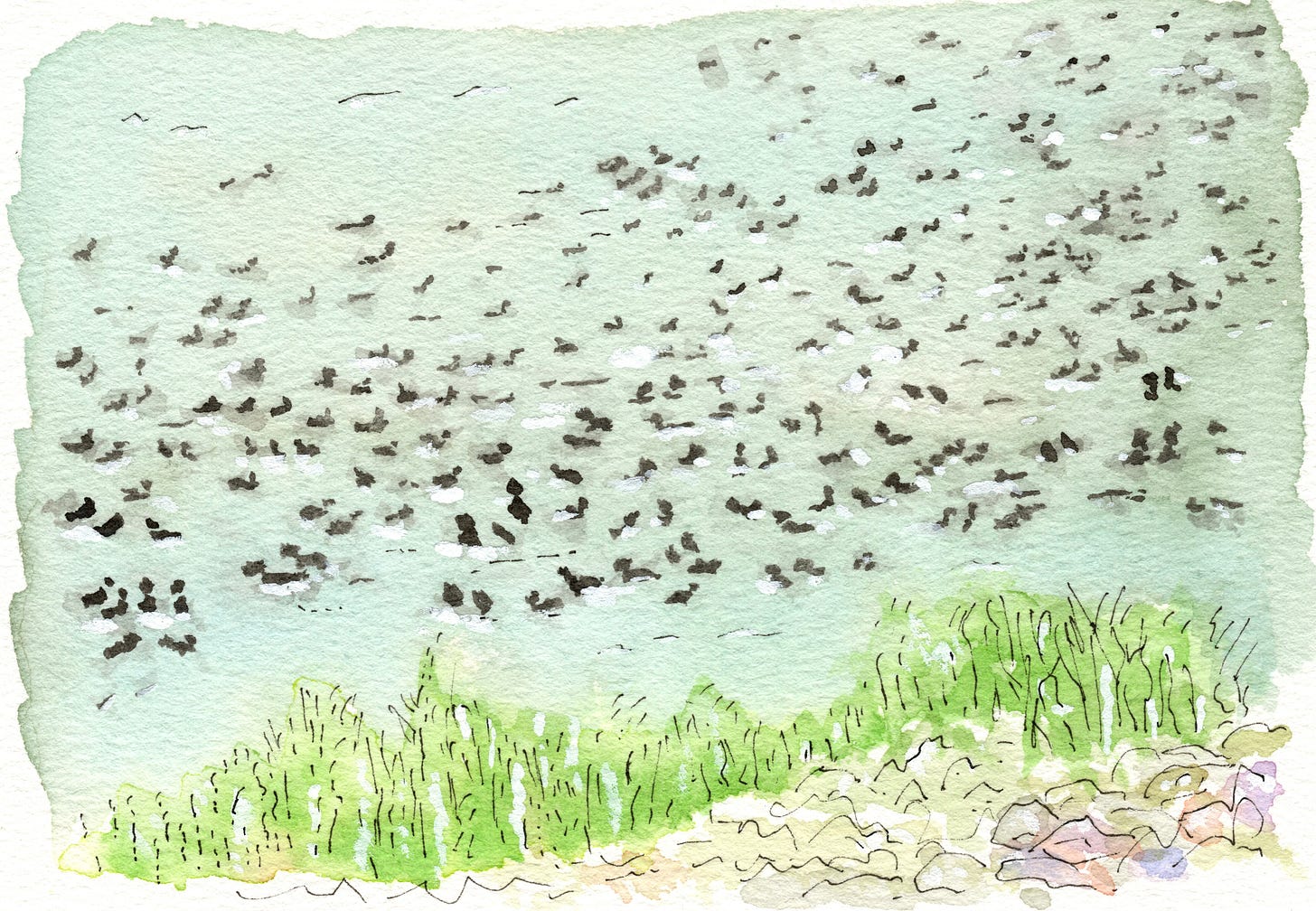

“Eared Grebes,” he said. “There are tens of thousands of them here right now. See?”

He pointed farther out where throngs of tiny dots bobbed on the water. They were birds that had come from the Canadian prairies and the Western US, drawn to shallow lake’s brine shrimp. Steve called it staging, a crucial phase where they fed, gained weight, and grew new feathers in preparation for their migration to the West Coast for winter. “Right now, they’re flightless. They’re molting,” he said.

Steve pulled his binoculars up to his eyes. He cupped his hands around the eyepieces, blocking out any light interference.

“Did you come out of the womb wearing binoculars?” I asked.

“I was eight, actually.”

Steve spent summers with his cousins at his grandmother’s cottage beside the Gatineau River in Quebec, he told me. He worshiped his cousin Rob and tagged along on hikes, eager to keep up. Rob shared his binoculars as they wandered through maple, oak, and hemlock forests, searching for birds.

One sunny morning, they canoed across the river toward an apple tree’s long branch hanging over an inlet. A pair of Eastern Kingbirds, male and female, swooped near their heads. As the canoe drifted beneath the branch, they found themselves staring directly into the kingbirds’ nest. They got the message and moved on.

It was his spark bird. The Eastern Kingbird, a grey and white songbird with a white-tipped tail, filled Steve with wonder. That moment ignited something in him. He became a zealous convert, forever searching for birds.

A spark bird is the first bird that opens your curiosity into their world. It’s as if you’ve never noticed them before, until one captures your attention. Suddenly you’re changed. The whole avian world unfolds before your eyes. For one person it might be spotting a Red-tailed Hawk perched on a tree branch, preening its feathers. For another, the Painted Bunting, dressed in its technicolor red, green, blue, and yellow. For Steve, it was the dapper Eastern Kingbirds fiercely protecting their nest.

Steve first focused on birds in Ontario, he told me. When he entered the Royal Military College of Canada he moved around the Canadian provinces and discovered more birds. His career then took him around the world to Europe, Russia, and the Middle East, where he added more bird species to his life list.

When I was young, I’d camp with my family on the Oregon coast and hike trails with my sister and brother. At our home, my dad fixed a railroad tie beam high up between two giant Douglas Fir trees. He hung a tire swing from it, and I would spend afternoons in that swing, looking up into the trees. But I can’t recall any birds I saw. I wasn’t looking for them. I didn’t have the same wonder Steve had. He was an explorer, and as I stood next to him on the shore of the Great Salt Lake I wondered if he would somehow change my life.

“Do you want to see the grebes up close?” he asked me.

Before I could answer, he grabbed his tripod and spotting scope from the trunk. He set them up effortlessly, peered through the scope and said, “Here, look!”

I closed one eye as I pressed my other against the eyepiece. The cool metal of the scope felt reassuring against my skin. Through the lens, I felt like I was right next to the bird. Its head, long neck, and back feathers were a glossy black, shimmering in the sunlight. The side feathers were a rich rufous, contrasting beautifully with the golden wisps of feathers that splayed back from its blazing red eyes. If David Bowie chose to be a bird, he would want to be an Eared Grebe, I thought.

“Wow,” I said. “Those feathers around the eye.”

“That’s its plumage,” Steve said. “It attracts a mate, but he’ll be losing it while he’s here during his molting stage.”

We left the causeway shores and drove around the island’s two-lane road amidst grasslands with tumbleweed. I inhaled the sweet scent of short, prickly mountain sage. Salt bushes burst with mustard-yellow flowers, adding cheerful color to the brown landscape. In the distance, I could see the urban sprawl of the Salt Lake valley, but I felt as if I’d traveled to another country.

Steve offered to drive home, and as I held his hand, I felt a little of the wonder he possessed.

Each time Steve visited me in Utah, he took the wheel, and we drove to Antelope Island. In winter, it looked like a pail of white paint had spilled all over the land. Snow covered everything except the lake.

“Why doesn’t it freeze? I asked.

“It’s the high salt content. The lake is always changing.”

As temperatures dropped, he explained, shrimp became less active, and fewer flies grazed on the lake. Phytoplankton grew, turning the lake green like pea soup. The smell that sometimes wafted through the valley was from the lake’s salt-loving bacteria emitting hydrogen sulfide.

Steve was fascinated by Utah’s Wasatch Front and its Great Salt Lake. More than 13,000 years ago, melt water from continental glaciers formed Lake Bonneville, which covered most of Utah and parts of Idaho and Nevada. Today, only a tiny remnant remains—the Great Salt Lake.

It wasn’t just the birds or me. Utah’s geology also drew Steve in.

“Our target bird today is the Chukar,” Steve said. “It’s a year-round resident here, and it’s a pretty cool bird to find.”

“How do you know all this?”

“I did my homework,” he said with a grin.

We rounded the bend away from the beach and up the hill to Buffalo Point. A monstrous black bison lay in the snow only five meters from the road. It breathed through its nose like a locomotive, emitting plumes of steam into the air. I expected the heat from its body to melt all the snow around it.

By the late 19th century, American bison were hunted to near extinction across North America. In 1893, twelve from a private herd in Texas were taken to Antelope Island, not to preserve and grow populations, but to be hunted for profit. Though the privately-owned herd grew to over 400, a final large-scale hunt in 1926 reduced the population to just 50. Public outcry pressured the owners to stop the hunting, and thanks to Utah’s purchase of the island and the bison in 1960, a thriving herd of 500-700 now roams freely at Antelope Island State Park.

Steve drove a little farther and pointed out animal tracks in the snow.

“Those are rabbits,” “those are antelope,” and “those are coyote,” he’d say. He knew because growing up at boarding school on the edge of the Canadian wilderness taught him those things.

Suddenly, he slammed on the brake. “Chukars!”

Birds the size of a football scampered from boulder to boulder near the side of the road, searching for seeds from bushes sticking out of the snow. A game bird native to the Middle East and Southern Asia, Chukars were introduced on Antelope Island as well as other high desert areas in the United States. Their gray bodies, black-and-white striped wings, and red legs stood out against the blanket of white. A bright red eye ring circled their dark eyes, and a black stripe ran across their eyes, which looked like little Zorro masks.

The birds noticed us and took cover behind the rocks. I turned to Steve. “Wow! I can’t believe it!”

My heart raced a little bit. Searching for a specific bird and finding it was intoxicating. More of this, please, I thought. Was I becoming addicted to this quest?

Another time when Steve visited, we left northern Utah’s palette of tans, browns, and sage and traveled four hours south where the earth turned red.

“It’s so different down here, right?” I said.

“The earth and rocks are red because of the iron oxide in the sandstone,” he explained. “It was an ancient desert millions of years ago, and the dunes were thousands of feet high. What we’re looking at are the eroded ancient dunes.” Steve always offered a geology lesson as we traveled through Utah. I was discovering that Utah was all about layers or strata. I saw new colors, both in the birds and in the landscape. There were new layers to me, too. A year earlier, I never would have found pleasure in driving to a lake to look at birds, and yet it’s where we spent most of our time. I never would have flown over to Scotland to rendezvous with a man I met online, and that, too, was now part of my own strata.

“Oh, I love Keats!” Steve said when he saw the poet’s name inscribed on our room door at the bed and breakfast where we were staying. Each room was named after a poet. His hands were full, carrying our weekend bags in each hand. As I turned the key and opened the door, I thought, Really? It didn’t match up to the adorable nerdy scientist I was falling for, but I loved this new revelation. Every moment with him was uncovering another layer in his strata.

The following evening after a long day of hiking at Zion, Steve sat in our room in a wing-back chair, flipping through a Birds of Utah field guide. I was tired with my eyes closed, then I heard:

“My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains

My sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk,

Or emptied some dull opiate to the drains

One minute past, and Lethe-wards had sunk:”

It was Steve’s voice.

“What is that?” I asked.

“Ode to a Nightingale. Keats.” He continued—

“'Tis not through envy of thy happy lot,

But being too happy in thine happiness,—

That thou, light-winged Dryad of the trees

In some melodious plot

Of beechen green, and shadows numberless,

Singest of summer in full-throated ease.”

He recited all eight stanzas almost like a whisper. His deep voice placed one word carefully after another. He paused a few times searching his memory for the next lines.

I floated on his every word and when he finished, I couldn’t speak for a few seconds. Then I asked, “How do you know that?”

“When I was in the army, we had to stand and march for hours. I was bored. I copied poetry on index cards so I could memorize them.” He chuckled. “I didn’t want any of the others to know what I was doing, so on the other side of each card I wrote calculus formulas. In case anyone asked, I’d show them that side.”

The moment cracked me open wide and allowed me to fall more deeply in love. We both fell, like a pair of Bald Eagles that fly high into the sky, clasp their talons together, and spiral down in a free fall, holding each other during their courtship ritual.

Steve continued to visit each month, and sometimes I’d visit him in Canada. But Utah, he told me, was where it felt like home.

He wasn’t coming just for the birds.

Our lives melded each time he visited. After I picked him up at the airport, we’d dine at our favorite Thai restaurant. He’d bring my favorite donut holes from Tim Hortons, the legendary Canadian donut chain. We’d eat them while we played Scrabble with sticky fingers at the kitchen table. And I was excited to visit Antelope Island to see how it had changed.

Spring brought green prairie grass to the island, and thousands of birds dotted the Great Salt Lake. I learned that the hyper-saline ecosystem at the lake is the basis of the whole food chain. It offered an open buffet for the millions of migrating birds. The blue green water filled with algae and attracted brine shrimp and brine flies, creating a vast protein food factory for birds at the intersection on their migration routes. While some shorebirds were on a mad rush to nest in prairies, others were making their way to the high arctic. They intersected at the Great Salt Lake where they ate as much as they could before continuing their journey.

The Eared Grebes were back from their wintering grounds on the California coast. It was as though I had just seen a friend who had been away for a while. As I witnessed the life cycle of these birds, my aperture began to widen.

At the southeast end of the island was Fielding Gar Ranch where giant Cottonwood trees shaded the historical 1840s adobe ranch house. A young boy and his parents walked through the rooms on a self-guided tour and a family of four set up their lunch on a picnic table in front of the house. A teenager wandered, holding his phone with his arm stretched out, probably looking for a cell signal.

Reliable natural springs nourished a fresh, verdant oasis for migrating songbirds—sparrows, warblers, thrushes, orioles, tanagers, and flycatchers—winged travelers crossing the high desert.

A group of birders craned their necks, binoculars pressed to their eyes, scanning for birds flitting around tree branches. Unsure which birds to seek, I watched for anything that stirred. Steve spotted birds with ease, calling them out and pointing their location. When the bird stood still, he shared his binoculars so I could get a closer look. He quickly identified details that differentiated them: The White-crowned Sparrow’s crisp head stripes, the Song Sparrow’s dark chest spot, and the Fox Sparrow’s russet hue.

After more than a year of flying back and forth, our relationship had settled into a rhythm. Utah’s summer heat revealed Great Salt Lake’s mud flats, where salt crystals shimmered across the water’s surface. Despite the summer calendar, fall migration was already underway, Steve explained.

Wilson’s Phalaropes arrived in waves. The first, a million strong, were females crowding the lake. Having laid their eggs in prairie nests, the females deparated, leaving incubation and child-rearing to the males. In a month, the males would arrive in the second wave with their young. Half of the world’s population of Wilson’s Phalaropes paused at the lake, fattening up before their long migration to wintering grounds off the coast of South America.

As we drove, the flaxen prairie grass lay back against the earth, weary from the relentless summer heat. Golden sunflowers stretched skyward, dancing in the welcome breeze. On Antelope Island, time stretched wide, pulling me into a new kind of attention where my wonder for nature and love for Steve deepened. The thought of marriage wove itself into our conversations, light but unmistakable.

On Antelope Island, I discovered my Spark Bird. It wasn’t the Chukars, Eared Grebes, Fox Sparrow, or even the Wilson’s Phalaropes that stirred my wonder and curiosity about their avian world. It was something more. It was life altering. Just like any spark, it ignited something bigger. Through Steve, the world widened. He captured my attention, and I was changed. He was my Spark Bird.

This essay, Spark Bird, won a 2025 Solas Award Best Travel Writing Silver in the Love Story category.

A very fine piece. I love the idea of "a spark bird" and how there are so many similar spark moments or choices me make in our lives. We just have to pay attention.

Loved this!! The ending…so perfect!! Beautiful storytelling 🌈🐦🫶